The Sequester has arrived–mostly unexpected, entirely unwelcome and apparently it intends to hang around a while. What does it mean for landlords of federal-leased properties? Fortunately, probably not much. At least not much new. The federal government has been staggering from crisis to crisis for years.

The Sequester has arrived–mostly unexpected, entirely unwelcome and apparently it intends to hang around a while. What does it mean for landlords of federal-leased properties? Fortunately, probably not much. At least not much new. The federal government has been staggering from crisis to crisis for years.

A Look at the Cuts

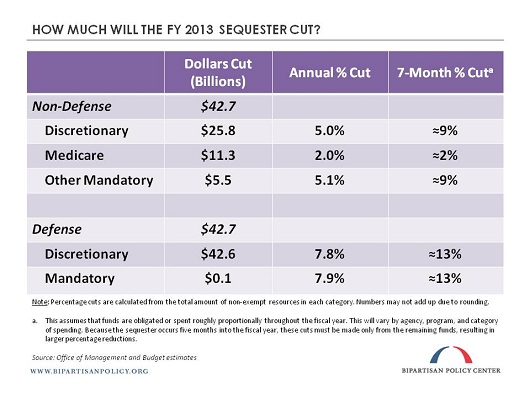

The great concern with sequestration is not that it applies $1.2 trillion of cuts to the (growth of the) federal budget over the next 10 years. It’s that it does so indiscriminately, at a time when the economy remains fragile. This year alone, the sequester will deal the federal budget an $85 billion hit. That’s a big number by any measure, except perhaps when you compare it to the president’s overall federal budget, which is $3.8 trillion in fiscal year 2013.

All of a sudden $85 billion looks small; yet, almost two-thirds of federal spending goes to mandatory payments for entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, and interest payments on the national debt. Social Security and Medicaid are fully exempt from the sequester and “cuts” to Medicare serve only to limit future cost increases. Further, federal pay is exempt as are veterans benefits and military pensions. When you get right down to it, in the absence of a Grand Bargain to reform entitlement spending (unlikely to occur anytime soon), the cuts primarily impact discretionary spending. This is where the $85 billion sting will be felt most.

The Impact on Federal-Leased Buildings

Real estate costs reside in the discretionary budget, so that is a concern. Leases are federal contracts, just like purchases of weapons systems or pencils; and we expect that contracts will bear much of the brunt of the sequester. The reason is that most government contracts are cancellable. This is due to the Antideficiency Act, a law that restricts any federal officer or employee from obligating the government to a contract for which funds have not already been appropriated. The Antideficiency Act is the reason that multi-year federal contracts may typically be cancelled (and, conversely, why contracts are often structured with a one-year base term and multiple one-year options). Surprisingly there are federal leases–even long term ones–that are cancelable due to “subject to annual appropriations” clauses. Some landlords must be experiencing insomnia.

Fortunately, most traditional federal office and industrial leases are administered by the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) and they are immune to the sequester. The GSA manages the Federal Buildings Fund, a multi-billion dollar revolving fund established specifically to accommodate multi-year lease contracts. Since the Federal Buildings Fund is paid in through rents from the agencies who occupy the leased space, it is self-sustaining. Further, GSA is a self-funded independent agency, also exempt from the sequester. GSA signs the leases and then, through occupancy agreements, provides that space for use by tenant agencies. In essence, GSA is a sublandlord.

Long Term Effects

If there is peril in GSA’s occupancy agreement structure it is that most of these agreements allow the tenant agencies to give their space back to GSA with just 120 days notice–this despite the remaining term on the lease. That won’t impact property owners directly because GSA must continue to pay rent, but it could create vacancies within the GSA’s inventory that the government will seek to backfill. If the Sequester lingers we can expect that these backfill spaces to develop a growing gravitational force, pulling tenancy out of other buildings as leases roll. When competing against fallow government space, the advantages of being the incumbent landlord are often rendered moot.

Yes, in the long run federal downsizing could weaken the market but that won’t be the sole fault of the sequester. There are many other factors to share the blame: the federal government has operated primarily under a continuing resolution since 2010 putting long term real estate planning in limbo; OMB issued an edict nearly a year ago restricting any net growth in the federal inventory, and; Congress has declared that it will require every prospectus lease to demonstrate savings through reduced square footage and improved space utilization. The move towards reduced square footage has already begun. It is a worrisome trend but it will be with us, with or without the sequester.

The other long term effects of sequestration may be more appealing to lessors. Among them, it is clear that Congress will continue to restrict GSA’s obligational authority, preventing the agency from making meaningful investments in major construction and renovation projects. This virtually guarantees that GSA will continue to rely heavily on leased space–and perhaps capital from lessors financed through the lease structure.

Short Term Effects

In the near term we expect the government to be immobilized by uncertainty and, frankly, lack of funds. No one knows how long the sequester will last before Congress finds a more sensible approach to deficit reduction. One unfortunate consequence of this is that the trend towards shorter lease terms will continue; yet, renewal probability should remain high. Shorter terms improve the incumbent advantage, virtually ensuring a renewal. In some cases agencies may elect to downsize upon renewal but we can blame that on budget conditions that pre-dated the Sequester. All signs indicate that the government’s near term response to the sequester will be cancellation of contracts and furloughs. Neither of these will have any direct impact on space needs.

The challenge for lessors will be to:

1) Exercise patience. No one one can predict if, when or how sequestration will transition to a more durable budget policy.

2) Engage your tenants early and often. Their needs may ultimately require space reconfiguration that they cannot afford. Ensure that your capital budgeting anticipates your tenants’ needs.

3) Think creatively. Never has there been a better time to explore renewal and “blend and extend” structures but the government won’t approach you with those solutions. You need to craft and deliver them yourself.