The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 has sparked a faint glow of optimism that agencies will plan more strategically for their space needs in the coming years. Last spring, a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report estimated that maintenance and operations of unused federal courthouse space cost the government $51 million per year, and in September, the Judicial Conference of the US voted to require a 3% reduction in space inventory by the end of FY 2018. Now a new report from the GAO explicitly recommends better planning by the GSA and the judiciary for future uses of un-needed courthouses.

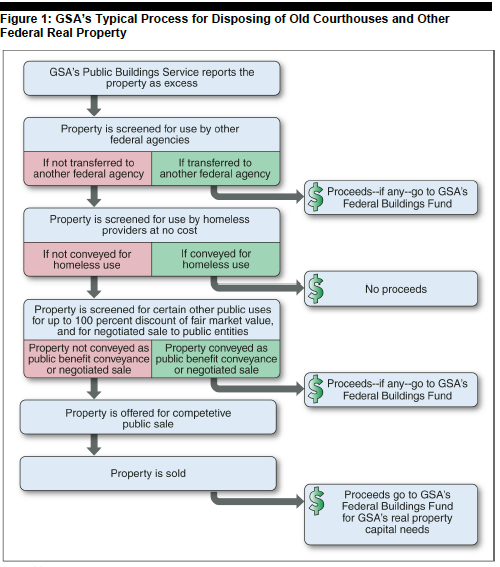

Since 1993, 66 old courthouses have been replaced or supplemented by new facilities built by the GSA. That agency, not the judiciary, determines the fate of old courthouses, based on considerations of building condition, historic or architectural significance, future occupancy interest by the judiciary, local market conditions and needs of other federal tenants in the area. The Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949 provides the basic process for determining how to dispose of courthouses deemed excess, as shown in the figure below from the GAO report. Notably, if the GSA fails to identify local, state or federal government or other public use for a property, it can begin planning for a private sale.

The GAO found that it takes about 1.4 years for the GSA to dispose of unneeded courthouses, attributing many delays to aging structures with historic value that do not meet court security standards. With a goal of making more efficient use of federal real estate, the GAO examined GSA and judiciary management in three areas:

The GAO found that it takes about 1.4 years for the GSA to dispose of unneeded courthouses, attributing many delays to aging structures with historic value that do not meet court security standards. With a goal of making more efficient use of federal real estate, the GAO examined GSA and judiciary management in three areas:

- How retained courthouses are used and related challenges;

- How excess courthouses are disposed of; and

- How the future use of old courthouses is considered in GSA proposals for new courthouses.

Data were collected on 66 courthouses replaced or supplemented in the past 2 decades, and GSA officials, judges and judicial officials were interviewed for their perspectives on courthouse disposal and reuse. Also, 13 courthouses, representing a mix of retained and disposed buildings around the country, were investigated as case studies.

The results of the analysis, conducted between November 2011 and September 2012, are eye opening. By the end of the study, nearly 2/3 of the 66 courthouses were still owned by the federal government. Thirty-six were occupied by the judiciary and other federal tenants, 3 were vacant and 1 was under renovation. Excluding the building closed for renovations, about 14% of the total space was vacant, compared with the 4.8% vacant space average in all federally-owned buildings in 2012. Case studies of old courthouses revealed that high costs and complexity of renovations often lead to underutilized space at many locations, while parking limitations at a California courthouse limited its appeal to new federal tenants. Space needs within the judiciary have also changed, leading often to suboptimal use. For example, the report questions the need for 17,000 SF of library space in a Richmond courthouse when online legal research is increasingly common and new courthouse designs allocate about 9,200 SF. Full building and partial vacancies contribute to net-operating-income losses for many old courthouses and deplete the Federal Buildings Fund, which the GSA uses to maintain and improve its whole real estate portfolio.

The GSA sold 14 and exchanged 3 old courthouses, realizing about $20 million from sales plus land for new courthouses. Future uses for the disposed buildings included affordable housing, state and local government offices, a juvenile justice center and a hotel. Most buildings with historical significance were conveyed with requirements that historic features be preserved during re-use. Case studies again were revealing, as in the decade-long efforts to dispose of an old Kansas City courthouse. Opened in 1939 and vacated in 1998, the building’s historical significance led the GSA to retain ownership but no practical re-use was identified. Not until 2008 was the City of Kansas City granted a public building conveyance. Screening of excess real property for use by organizations for the homeless, as required by McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, can also be protracted and complex, and the GAO did not find any old courthouses re-purposed to benefit homeless people.

In light of the costs and complexities of courthouse reuse and disposal, the GAO report concludes that comprehensive planning is essential to achieve more efficient use of government resources. The GSA is not currently required by law to provide plans for old courthouses when submitting new courthouse proposals to Congress, but the GAO contends that Congress and other stakeholders need to know more about the potential fate of old courthouse space to make informed decisions about capital planning. The GAO report specifically recommends that the GSA and the judiciary include specific plans in proposals for new courthouses for reuse or disposal, including needed renovations, related costs and anticipated issues that could cause difficulties and delays. The judiciary and the GSA concurred with the recommendation in letters included with the report. In his response, GSA Administrator Dan Tangherlini supports the effort to improve transparency in planning, saying the GAO recommendation “will enable congressional decision makers to more accurately assess the viability of GSA’s proposals and the full costs of those proposals to the American taxpayers.”